Marionette, Act I: We’ve got Firefox on a string

08 Jul 2016As you may already know, I’m spending my summer interning with Mozilla’s Enginering Productivity team through the Outreachy program. Specifically, the project I’m working on is called Test-driven Refactoring of Marionette’s Python Test Runner. But what exactly does that mean? What is Marionette, and what does it have to do with testing?

In this two-part series, I’d like to share a bit of what I’ve learned about the Marionette project, and how its various components help us test Firefox by allowing us to automatically control the browser from within. Today, in Act I, I’ll give an overview of how the Marionette server and client make the browser our puppet. Later on, in Act II, I’ll describe how the Marionette test harness and runner make automated testing a breeze, and let you in on the work I’m doing on the Marionette test runner for my internship.

And since we’re talking about puppets, you can bet there’s going to be a hell of a lot of Being John Malkovich references. Consider yourself warned!

How do you test a browser?

On the one hand, you probably want to make sure that the browser’s interface, or chrome, is working as expected; that users can, say, open and close tabs and windows, type into the search bar, change preferences and so on. But you probably also want to test how the browser displays the actual web pages, or content, that you’re trying to, well, browse; that users can do things like click on links, interact with forms, or play video clips from their favorite movies.

Because let's be honest, that's like 96% of the point of the internet right there, no?

These two parts, chrome and content, are the main things the browser has to get right. So how do you test them?

Well, you could launch the browser application, type “Being John Malkovich” into the search bar and hit enter, check that a page of search results appears, click on a YouTube link and check that it takes you to a new page and starts playing a video, type “I ❤️ Charlie Kaufman and Spike Jonze” into the comment box and press enter, check that it submits the text…

And when you’re done, you could write up a report about what you tested, what worked and what didn’t, and what philosophical discoveries about the nature of identity and autonomy you made along the way.

Am I the puppet? AM I?

Being John Malkovich via COADA on Tumblr

Now, while this would be fun, if you have to do it a million times it would be less fun, and your boss might think that it is not fun at all that it takes you an entire developer-hour to test one simple interaction and report back.

Wouldn’t it be better if we could magically automate the whole thing? Maybe something like:

import magical_automated_browser as client

client.navigate("https://www.youtube.com")

client.find_element(By.ID, "search-bar").send_keys("Being John Malkovich")

client.find_element(By.ID, "search-button").click()

# etc., etc.SPOILER ALERT: We can, thanks to the Marionette project!

What is Marionette?

Marionette refers to a suite of tools for automated testing of Mozilla browsers. One important part of the project is an automation framework for Gecko, the engine that powers Firefox. The automation side of Marionette consists of the Marionette server and client, which work together to make the browser your puppet: they give you a nice, simple little wooden handle with which you can pull a bunch of strings, which are tied to the browser internals, to make the browser and the content it’s displaying do whatever you want. The client.do_stuff code above isn’t even an oversimplification; that’s exactly how easy it becomes to control the browser using Marionette’s client and server. Pretty great right?

But Marionette doesn’t stop there! In addition to the client & server giving you this easy-peasy apparatus for automatic control of the browser, another facet of the Marionette project - the test harness and runner - provides a full-on framework for automatically running and reporting tests that utilize the automation framework. This makes it easy to set up your puppet and the stage you want it to perform on, pull the strings to make the browser dance, check whether the choreography looked right, and log a review of the performance. I can see the headline now:

Screenwriter Charlie Kaufman enthralls again with a brooding script for automated browser testing

You: GROAN. That's a terrible joke.

Me: Sorry, it won't be the last. Hang in there, reader.

Being John Malkovich via the dissected frog (adapted with GIFMaker.me)

As I see it, the overall aim of the Marionette project is to make automated browser testing easy. This breaks down into two main tasks: automation and testing. Here in Act I, we’ll investigate how the Marionette server and client let us automate the browser. In the next post, Act II, we’ll take a closer look at how the Marionette test harness and runner make use of that automation to test the browser.

How do Marionette’s server and client automate the browser?

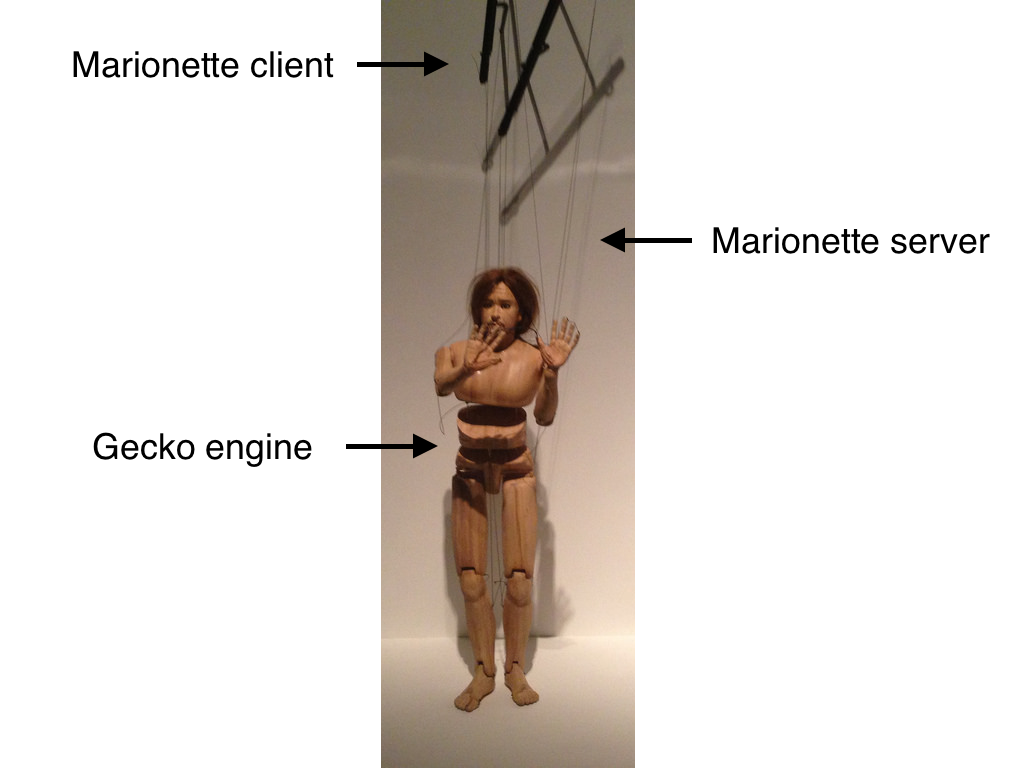

A real marionette is composed of three parts:

- a puppet

- strings

- a handle

This is a great analogy for Marionette’s approach to automating the browser (I guess that’s why they named it that).

The puppet we want to move is the Firefox browser, or to be precise, the Gecko browser engine underlying it. We want to make all of its parts – windows, tabs, pages, page elements, scripts, and so forth – dance about as we please.

The handle we use to control it is the Marionette client, a Python library that gives us an API for accessing and manipulating the browser’s components and mimicking user interactions.

The strings, which connect handle to puppet and thus make the whole contraption work, are the Marionette server. The server comprises a set of components built in to Gecko (the bottom ends of the strings), and listens for commands coming in from the client (the top ends of the strings).

Photo adapted from "Marionettes from Being John Malkovich" by Alex Headrick, via Flickr

The puppet: the Gecko browser engine

So far, I’ve been talking about “the browser” as the thing we want to automate, and the browser I have in mind is (desktop) Firefox, which Marionette indeed lets us automate. But in fact, Marionette’s even more powerful than that; we can also use it to automate other products, like Firefox for Android (codenamed “Fennec”, so cute!) or FirefoxOS/Boot to Gecko (B2G). That’s because the puppet Marionette lets us control is actually not the Firefox desktop browser itself, but rather the Gecko browser engine on top of which Firefox (like Fennec, and B2G) is built. All of the above, and any other Gecko-based products, can in principle be automated with Marionette.1, 2

Just choose your puppet!

Adapted from "Marionettes from Being John Malkovich" by Alex Headrick via Flickr, with logos from @FennecNightly, Firefox branding, and B2G OS.

So what exactly is this Gecko thing we’re playing with? Well, I’ve already revealed that it’s a browser engine - but if you’re like me at the beginning of this internship, you’re wondering what a “browser engine” even is/does. MDN explains:

Gecko’s function is to read web content, such as HTML, CSS, XUL, JavaScript, and render it on the user’s screen or print it. In XUL-based applications Gecko is used to render the application’s user interface as well.

In other words, a browser engine like Gecko takes all that ugly raw HTML/CSS/JS code and turns it into a pretty picture on your screen (or, you know, not so pretty - but a picture, nonetheless), which explains why browser engines are also called “layout engines” or “rendering engines”.

And see that bit about “XUL”? Well, XUL (XML User interface Language) is a markup language Mozilla came up with that lets you write application interfaces almost as if they were web pages. This lets Mozilla use Gecko not only to render the websites that Firefox lets you navigate to, but also to render the interface of Firefox itself: the search bar, tabs, forward and back buttons, etc. So it’s safe to say that Gecko is the heart of Firefox. And other applications, like the aforementioned Fennec and FirefoxOS, as well as the Thunderbird email client.

But wait a minute; why do we have to go all the way down to Gecko to control the browser? It’s pretty easy to write add-ons to control Firefox’s chrome or content, so why can’t we just do that? Well, first of all, security issues abound in add-on territory, which is why add-ons typically run with limited privileges and/or require approval; so an add-on-based automation system would likely give under- or over-powered control over the browser. But in fact, the real reason Marionette isn’t an add-on is more historical. As browser automation expert and Mozillian David Burns explained at SeleniumConf 2013, Marionette was originally developed to test FirefoxOS, which had the goal of using Gecko to run the entire operating system of a smartphone (hence FirefoxOS being codenamed Boot to Gecko). FirefoxOS didn’t allow add-ons, so the Marionette team had to get creative and build an automation solution right into Gecko itself. This gave them the opportunity to make Marionette an implementation of the WebDriver specification, a W3C standard for a browser automation interface. The decision to build Marionette as part of Gecko rather than an add-on thus had at least two advantages: Marionette had native access to Gecko and didn’t have to deal with add-on security issues,3 and by making Marionette WebDriver-compliant, Mozilla helped advanced the standardization of browser automation.

So that’s why it’s Gecko, not Firefox, that Marionette ties strings to. In the next section, we’ll see what those knots look like.

The strings: the Marionette server

As mentioned in the previous section, Marionette is built into Gecko itself. Specifically, the part of Marionette that’s built into Gecko, which gives us native access to the browser’s chrome and content, is called the Marionette server. The server acts as the strings of the contraption: the “top end” listens for commands from the handle (i.e. the Marionette client, which we’ll get to in the next section), and the “bottom end” actually manipulates the Gecko puppet as instructed by our commands.

The code that makes up these strings is written in JavaScript and lives within the Firefox codebase at mozilla-central/testing/marionette. Let’s take a little tour, shall we?

The strings are embedded into Gecko via a component called MarionetteComponent, which, when enabled,4 starts up a MarionetteServer, which is the object that most directly represents the strings themselves.

MarionetteComponent is defined in components/marionettecomponent.js (which, incidentally, includes the funniest line in the entire Marionette codebase), while

MarionetteServer is defined in the file server.js. As you can see in server.js, MarionetteServer is responsible for tying the whole contraption together: it sets up a socket on a given port where it can listen for commands, and uses the dispatcher defined in dispatcher.js to receive incoming commands and send data about command outcomes back to the client. Together, the server and dispatcher provide a point of connection to the “bottom end” of the strings: GeckoDriver, or the part of Marionette that actually talks to the browser’s chrome and content.

GeckoDriver, so named because it’s the part of the whole Marionette apparatus that can most accurately be said to be the part automatically driving Gecko, is defined in a file that is unsurprisingly named driver.js. The driver unites a bunch of other specialized modules which control various aspects of the automation, pulling them together and calling on them as needed according to the commands received by the server.

Some examples of the “specialized modules” I’m talking about are:

element.js, which maps out and gives us access to all the elements on the pageinteraction.jsandaction.js, which help us mimic mouse, keyboard, and touchscreen interactionsevaluate.js, which lets us execute JavaScript code

With the help of such modules, the driver allows us to grab on to whatever part of the browser’s chrome or content interests us and interact with it as we see fit.

The Marionette server thus lets us communicate automatically with the browser, acting as the strings that get tugged on by the handle and in turn pull on the various limbs of our Gecko puppet. The final part of the puzzle, and subject of the next section, is the handle we can use to tell Marionette what it is we want to do.

The handle: the Marionette client

For us puppeteers, the most relevant part of the whole marionette apparatus is the one we actually have contact with: the handle. In Marionette, that handle is called the Marionette client. The client gives us a convenient API for communicating with Gecko via the Marionette server and driver described in the previous section.

Written in user-friendly Python,5 the client is defined in the confusingly-named client/marionette_driver directory inside of mozilla-central/testing/marionette. The client and its API are described quite clearly in the refreshingly excellent documentation, which includes a quick tutorial that walks you through the basic functionality.

To start pulling Marionette’s strings, all we need to do is instantiate a Marionette object (a client), tell it to open up a “session” with the server, i.e. a unique connection that allows messages to be sent back and forth between the two, and give it some commands to send to the server, which (as we saw above) executes them in Gecko. And of course, this assumes that the instance of Firefox (or our Gecko-based product of choice) has Marionette enabled,4 i.e. that there’s a Marionette server ready and waiting for our commands; if the server’s disabled, the strings we’re pulling won’t actually be connected to anything.

The commands we give can either make changes to the browser’s state (e.g. navigate to a new page, click on an element, resize the window, etc.), or return information about that state (e.g. get the URL of the current page, get the value of a property of a certain element, etc.). When giving commands, we have to be mindful of which context we’re in, i.e. whether we’re trying to do something with the browser’s chrome or its content. Some commands are specific to one context or the other (e.g. navigating to a given URL is a content operation), while others work in both contexts (e.g. clicking on an element can pertain to either of the two). Luckily, the client API gives us an easy one-liner to switch from one context to another.

Let’s take a look at a little example (see the docs for more):

# Import browser automation magic

from marionette import Marionette

from marionette_driver.by import By

# Instantiate the Marionette (client) class

client = Marionette(host='localhost', port=2828)

# Start a session to talk to the server

# (otherwise, nothing will work because the strings aren't connected)

client.start_session()

# Give a command and check that it worked

client.navigate("https://www.mozilla.org")

assert "building a better Internet" in client.title

# Switch to the chrome context for a minute (content is default)

with client.using_context(client.CONTEXT_CHROME):

urlbar = client.find_element(By.ID, "urlbar")

urlbar.send_keys("about:robots")

# try this one out yourself!

# Close the window, which ends the session

client.close()It’s as simple as that! We’ve got an easy-to-use, high-level API that gives us full control over the browser, in terms of both chrome and content. Given this simple handle provided by the client, we don’t really need to worry about the mechanics of the server strings or the Gecko puppet itself; instead, we can concern ourselves with the dance steps we want the browser to perform.

Arabesque? Pirouette? Pas de bourrée? You name it!

Being John Malkovich via ScreenplayHowTo

The browser is our plaything! Now what?

So now we’ve seen how the Marionette client and server give us the apparatus to control the browser like a puppet. The client gives us a simple handle we can manipulate, the server ties strings to that handle that transmit our wishes directly to the Gecko browser engine, which dances about as we please.

But what about checking that it’s got the choreography right? Well, as mentioned above, the client API not only lets us make changes to the browser’s chrome and content, but also gives us information about their current state. And since it’s just regular old Python code, we can use simple assert statements to perform quick checks, as in the example in the last section. But if we want to test the browser and user interactions with it more thoroughly, we could probably use a more developed and full-featured testing framework.

ANOTHER SPOILER ALERT (well OK I actually already spoiled this one): the Marionette project gives us a tool for that too!

In Act II of this article, we’ll explore the Marionette test harness and runner, which wrap the server-client automation apparatus described here in Act I in a testing framework that makes it easy to set the stage, perform a dance, and write a review of the performance. See you back here after the intermission!

Sources

- The brains of Mozillians David Burns, Maja Frydrychowicz, Henrik Skupin, and Andreas Tolfsen. Many thanks to them for their feedback on this article.

- From FirefoxDriver to Marionette, Mozilla pulls the strings - Jonathan Griffin & David Burns, SeleniumConf 2013

- Automating your browser-based testing using WebDriver - Simon Stewart, Google Tech Talks 2012

- The Marionette codebase and documentation - Mozilla

Notes

1 Emphasis on the “in principle” part, because getting Marionette to play nicely with all of these products may not be trivial. For example, my internship mentor Maja has been hard at work recently on the Marionette runner and client to make them Fennec-friendly. ↩

2 If you’re interested in automating a browser that doesn’t run on Gecko, don’t fret! Marionette is Gecko-specific, but it’s an implementation of the engine-agnostic WebDriver standard, a W3C specification for a browser automation protocol. Given a WebDriver implementation for the engine in question, any browser can in principle be automated in the same way that Marionette automates Gecko browsers. ↩

3 In fact, Marionette’s built-in design makes it able to circumvent the add-on signing requirement mentioned earlier; this would be dangerous if exposed to end users (see 4), but comes in handy when Mozilla developers need to inject unsigned add-ons into development versions of Gecko browsers in automation. ↩

4 At this point (or some much-earlier point) you might be wondering:

Wait a minute - if the Marionette server is built into Gecko itself, and gives us full automatic control of the browser, isn’t that a security risk?

Indeed it is. That’s why, although Marionette is indeed built into Gecko and is thus, in a sense, laying dormant in every instance of a Gecko-based application like Firefox, it’s disabled by default so it can’t be used to control the browser. To run Firefox (or your puppet of choice) with Marionette enabled, you have to be running a Marionette-friendly build (i.e. a version for developers and not standard users) and specifically indicate that you want Marionette turned on when you launch the application. ↩

5 Prefer to talk to the Marionette server from another language? No problem! All you need to do is implement a client in your language of choice, which is pretty simple since the WebDriver specification that Marionette implements uses bog-standard JSON over HTTP for client-server communications. If you want to use JavaScript, your job is even easier: you can take advantage of a JS Marionette client developed for the B2G project. ↩